Healthy Roots (Modified From my Original Oratory)

“I am stronger than I am broken,” Roxanne Gay says in her memoir Hunger. It is the same thing I say to myself when I think about the scale under my bed, the calories on the back of a granola bar, the way my t-shirt sticks to my stomach. Growing up, I accepted that my body was something to be stretched and shrunk; that the constant search for weight loss was a natural factor of womanhood. Among my friends, it was the consensus for coping with our adolescent anxieties. Maybe you can’t stop your parents’ divorce, but you can always limit your calories. You can’t choose who wants to date you, but you can choose to obsess over workouts and new diets. My eating disorder consumed me. It was the center of my turning world, a sentiment I later heard from other girls also in recovery. We are built looking for control. The idea that we can control and apologize for our existence by making our physical selves smaller is something that has been passed down and pushed on us for as long as we have had consciousness of our bodies. Today, I’d like us to go through how and why the Western world has hyper-focused on the female body and the pressure to change it; what happens when we succumb to that pressure; and how we can set ourselves and future generations up for healthy relationships with our bodies and our minds.

Diet culture and the societal hierarchy of bodies came out of a blend of ancient Greece’s linkage of physical appearances to morals, and early Christian traditions of fasting and food restricting. This combination of influences emulated the idea that the thinner you are, the closer you are to holiness.

By the 18th century, prominent American figures such as Presbyterian minister Sylvester Graham began emphasizing the supposed connection between thinness, purity, and moral discipline. Ideologies like Graham’s soon solidified America’s new apprehensive approach to food. Companies quickly caught on to monetizing this starving movement as more and more women looked to weight loss as a way to become more societally attractive, respected, and conforming. The 20th century came with decadent and often dangerous diets. Cigarette brands found success in pushing smoking as a hunger suppressor. The Sleeping Beauty diet, which advised sleeping during mealtimes instead of eating, became popular through rumors that it was being used by celebrities such as Elvis Presley.

While these diets gave the illusion of advocating for health, they had a much more sinister execution.

This uprising of diet culture and focus on the female body was silently creating roots in systems of exploitation, with these roots being relied on to push and strengthen minority oppression.

The basis of all other negative consequences that come from this weight stigma is the equating of thinness with good, and of fatness with evil. When thinness becomes the ideal, we come to a false understanding that we as women are not meant to be more. The quieter, more docile, physically smaller we can make ourselves, the better job we are doing as the women society has boxed us into. By growing up in an ever-starving home, living in a tiny-body town, you assume that to ever be successful, less is more. This puts all of your humanity and worth into simply how much fat is around your bones. You grow up as if, as author Roxanne Gay eloquently puts it, “You are your body, nothing more, and your body should damn well become less.”

The body raised on this pedestal of glamorized thinness is often used to justify racial stereotypes and hierarchies. As Sabrina Strings’ book Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fatphobia cogently addresses the disrepute of fatness, “fat phobia isn't about health at all, but rather a means of using the body to validate race, class, and gender prejudice.” This created an extreme double standard, with White colonists seeing their own fatness as fortune and wealth to buy so much food, they condemned fat Black people as lazy, gluttonous, and sinful. Racism comes out of uplifting thinness, with the result of repressing and villanizing Black bodies.

Tying our self worth to our physical body changes not just how we fit into society, but how we fit into ourselves. This holy thinness creates a constant expectation for us to be changing, starving, slimming. And when we can’t meet these impossibly superficial demands, we may doubt that people with our natural bodies are deserving of the love, success, or confidence that we have. For as long as I can remember, I have always believed I am not good enough as I am; that there is always another girl out there thinner than me, prettier than me, that has more control than me. This rat race for “winning” Thinnest, Prettiest, Hungriest Girl spirals into depression, anxiety, and shame when you can’t achieve it.

Understanding the issues that follow the cult of thinness and dietary reserve bring us one step closer to overcoming it. Once we acknowledge the issue, we can take these steps to further heal it.

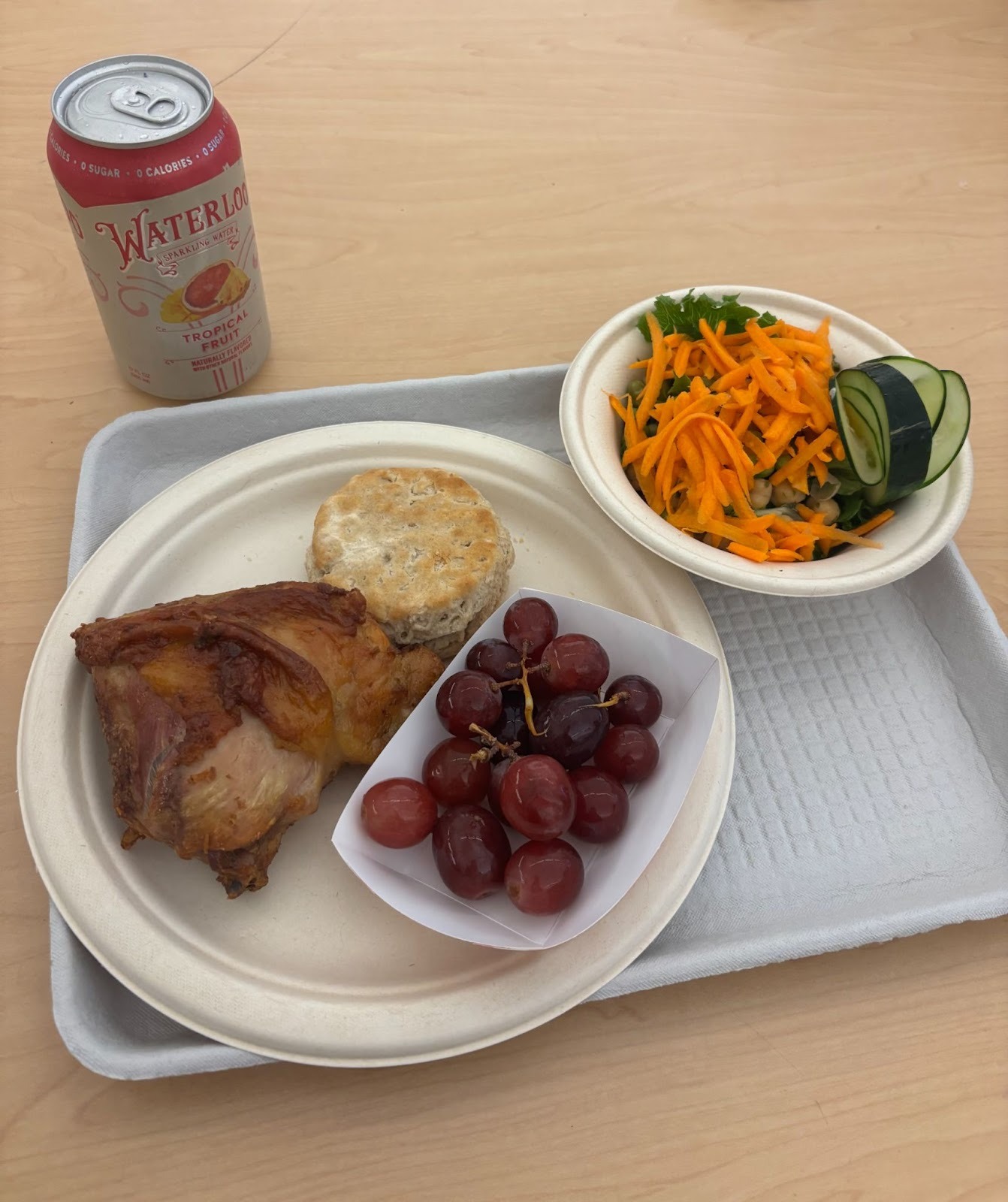

First, we must remember that our bodies are extensions of our minds. A lack of food in our bodies is a lack of fuel for our minds, and a lack of confidence in our minds creates insecurity and weakness in our bodies. The women that came before us didn’t make their mark because they were so quick at adding up their calories, or because they knew exactly how much they weighed. They nourished their bodies so their minds could thrive, and so a loving relationship between the two could be maintained.

With this, there should always be the reminder that there can be bad days. Cheesy, but relapse is a stage in recovery. Your insecurity doesn’t cancel out your progress. To think again of Roxanne Gay, “You are stronger than you are broken.” An insecure moment or behaviour can even be used as a positive learning opportunity, for you and others, as long as the moment doesn’t turn into a recurring pattern. Reaching out for help creates a chance to educate those you need help from. Awareness creates action.

Most importantly is to secure the same confidence we’ve just found in ourselves for future generations. To prevent the perversion and expectation of what our bodies should look like, we must create early roots in healthy body mindsets. An openness in how we discuss our bodies and our feelings about them sets up a positive mindset for generations to come.

Growing up in ever-dieting home, in a tiny-body town, I assumed it was completely normal to feel like my body wasn’t my own. After coming into my autonomy and confidence however I look, seeing the girls still living in my old and rotting mindset killed me. My message today is that as long as we treat our bodies with the care that we would treat the success of our futures, admit that giving into an insecurity doesn’t mean letting loose all bad behaviours, and if we do all we can to set the next generations up for eras of positivity and a cultural blossoming of self-esteem.